I have been struggling with the question for years. What things do you need to learn to become a competent bass player? I think I have a pretty good idea now.

First off, it's great if you have a good series of instructional videos that demonstrate the concepts herein. I use the Bass Lessons and Tips of Dale Titus, the best series of instructions I have found yet (and they're free). Dale has numerous videos on both music theory and bass technique, and they follow a logical sequence so that each builds on the one before. Each video is only a few minutes long and easy to watch.

See a list of his videos here. I will refer to them in this post.

Here are the steps.

1.

Learn the four strings, from top to bottom: E, A, D, G. Learn to tune your bass to these notes. I suggest using an inexpensive digital tuner, which you can buy in any music store. If you try to do it with an untrained ear, you are liable to break a string.

Your bass must be in tune before you try to learn anything.

2.

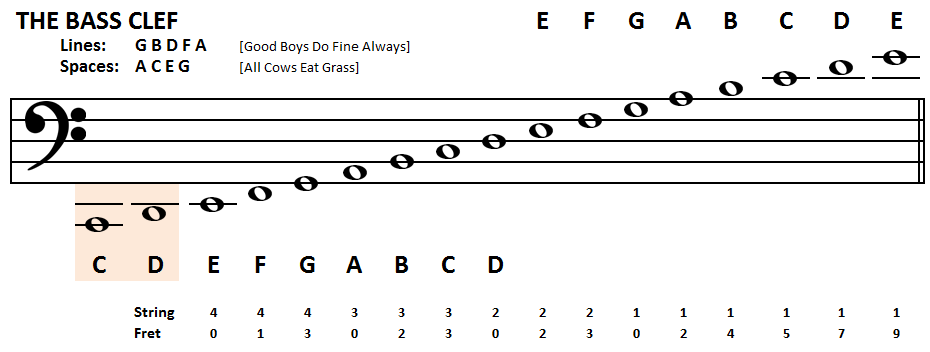

Learn how to name the notes on each string, moving from an open string to the first fret, second fret and so on. See the simple

chart on the bottom of this page. Know what a half step is and what a whole step is. Play each string from open to the 12th fret, naming the notes as you go. If it helps, sit down and draw the neck and the frets on a piece of paper and then name each note on each string.

3.

Learn to play the major scales. I suggest learning them in "Circle of 4ths Order," even if you don't have a clue as to what the Circle of 4ths is. (I'll explain later.) Consult the chart linked above. Learn to play each scale by memory; listen to the sounds of the notes, and say the notes out loud as you play them. (Watch Dale's videos

here,

here and

here.)

This will train your ear and also make you learn the bass neck. All bass runs, riffs and chords are made up of elements of the scales; learning the scales is like learning the alphabet. You can't write novels without learning the alphabet. You can't be a competent musician without learning the scales.

Note: If you're a beginner, don't worry about playing the scales in a fancy way -- just play them up and back down again. Once you learn the simple basics, you can expand from there, e.g. by playing the scales in thirds as Dale demonstrates in the videos.

Start with the C scale. Play it carefully, making each note clear, without string rattle. If you're new to bass, your fingertips may hurt a bit. Don't worry, they will soon toughen up -- it's part of the process. Play the scale forward and then backward, i.e. C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, C-B-A-G-F-E-D-C. It will sound like "do mi re fa sol la ti do, do ti la sol fa mi re do." (Remember when we learned that in third grade?)

After a week or so, you should be able to play all of the scales. Most of them are quite repetitive, you simply shift your start position to a different fret and play the same motions.

4.

Learn to play the major triads, or chords. When playing bass with a band, you are actually playing

chords, or parts of the scale. You don't play the entire scale, generally you just play three notes when playing major chords (from the major scale): you play the 1st (or root) note, the 3rd note, and the 5th note. Look at the chart of major scales. What are the notes in C major chord? They are C, E and G (1, 3 & 5). What are the chords in, say Bb (B Flat) major chord? Consult the chart. They are Bb, Db and F (B flat, D flat and F).

See this video on how to play major triads. It is quite instructive.

5.

Learn to play the natural minor scales. The minor scales are much like the major scales, except that the 3rd note and the 7th note are

flatted. That means they are played one fret back from where they are played on the major scale. The sound of the scale is different so listen carefully and memorize the sound.

6.

Learn to play the minor triads, or minor chords. A simple rule to remember is that a minor chord is just a major chord with a flatted third. So if C, E & G are C major chord, C minor chord would be C, Eb and G. (The "b" stands for flat). Remember, to flat a note you just move back one fret. If E is played on fret 7 of the A string (2nd string from the top), then Eb is played on fret 6.

See this video on how to play minor triads.

7.

Learn to play the Major Pentatonic Scale and the Minor Pentatonic Scale. These are short and easy to learn, but they further train the ear and provide the basis for some bass lines you will use later. Practicing them also helps develop your fingering skill.

8.

Learn the Modes. Modes are the major scales played in a different sequence. The different sequences produce very different sounds and further train the ear, increase knowledge of your neck, and provide the grist for bass grooves and bass lines you will learn later on (generally, ones you create yourself).

Dale Titus covers all of the modes.

Consult his link for a listing of all his videos. I will provide charts for each mode, to give you a visual reference and perhaps make it easier for you to learn them.

The modes are these:

- Ionian Mode -- Just the major scale, no difference.

- Dorian Mode -- The major scale, but you start on the 2 and play up to the octave and back again. For example, C major scale is C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C, and the Dorian mode of that scale is D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D.

- Phrygian Mode -- Major scale, but start with the 3rd, e.g. for C scale this would be E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E and back down again.

- Lydian Mode -- Major scale, start and end with the 4th (F, for C Scale).

- Myxolidian Mode -- Major scale but start and end with the 5th note in the scale, which is G for C scale.

- Aeolian Mode -- Start with the 6th note in the scale, which is A for C scale.

- Locrian Mode -- Start with the 7th note in the scale, which is B for C scale

9. Learn higher triads or chords, as follows:

- Diminished Triads

- Augmented Triads

- Major 7 Arpeggios (arpeggios are just chords, played one note at a time)

- Minor 7 Arpeggios

- Dominant 7 Arpeggios

- Minor 7 (Bb) Arpeggios

- Tritone Substitutions (different chords sometimes have the same notes as other chords, played in different sequences. Tritones allow you to substitute one chord for the other to create dissonant bass sounds -- great for jazz and improvization).

10. Learning to Apply All of the Above! The whole idea is to be able to play bass well, and these elements of knowledge will help get you there.

11. Other Things to Learn: Fingering and plucking techniques, slapping, harmonics, playing technique. See Dale Titus's site for a whole list of these.

Don't get discouraged or be impatient. If everyone could be a great bass player, it wouldn't be any fun. Add to your knowledge and skill a bit at a time. Imagine where you will be a month, three months, or a year from now! Don't worry about learning the higher skills until you have mastered the basic ones. (If Step 9 scares you, ignore it until you are ready.)

For questions, you can leave a comment or email me at stogiechomper "at" gmail.com.

UPDATE: Dale Titus has left Dana B Goods where his great lessons are linked. He is now teaching private bass lessons from his home in Folsom, California.

His website is here. You can contact him through his website.